Net of Nature

Trails

Campo Azálvaro Nature Trail

Description

A gully leading to the moor

The walled city of Ávila, declared a World Heritage Site, was, during mediaeval times, one of the main cities of Castile thanks to trade and to the thriving textile industry that was developed around wool. In this period, thousands of heads of merino sheep crossed its walls following the paths of the numerous drovers’ roads, many of which are still protected to this very day. One of the most important was the Cañada Real Soriana Oriental and today one of its sections, known as the Campo Azálvaro Nature Trail, continues to link the city of Ávila with this region as it did then.

The route begins on the outskirts of the capital, very close to the AV-500 highway, which links Ávila to El Espinar, level with kilometre 2, next to the last houses on the “Las Hervencias” housing estate.

A few metres after the beginning of the trail, there is an interpretative panel describing its route, itinerary, distances and most outstanding points and, on its right, in the landscape in the background, a hill with several telecommunications antennae.

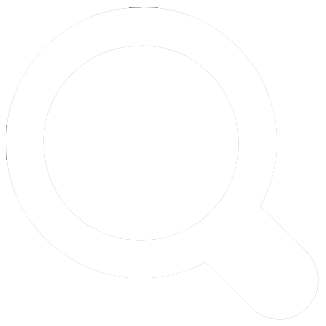

A few metres further on, the trail turns leftwards, in a south-westerly direction, where you can see a bicycle thoroughfare sign. It then continues up a gentle slope that enters an area of oak trees.

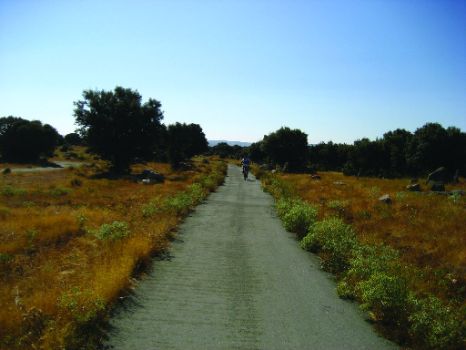

Further on, you come to a natural terrace, from where you can contemplate the meadows of Aldeagordillo and of El Gansino, in front of a magnificent pastured Holm oak grove. After a well-deserved rest, the route continues downwards towards a landscape featuring rocky areas and large lumps of granite, where the Holm oak grove gives way to a brushwood landscape formed of lavender (Lavandula stoechas), broom (Retamasp.) and Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) in one of the flattest sections of the trail.

Once you have reached kilometre four, another 2-kilometre gentle descent leads you to the nearby town of Bernuy-Salinero, a must-stop site on the trail. In this section, you can usually see the circular flight of Griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus) and, on occasions, even the sporadic black vulture (Aegypius monachus). Several intersections on the trail announce the proximity of this town, which you finally enter via an alleyway that leads to the fountain square, one of the only two points on the route where you can fill up with water.

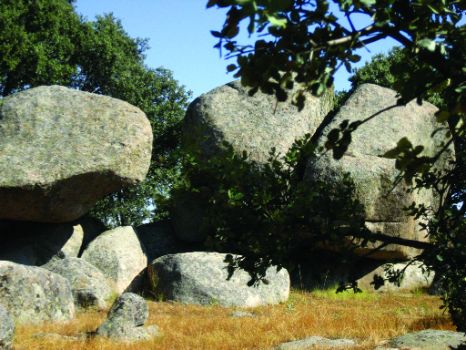

In the town centre, it is worth visiting the church of San Pedro Apóstol, which preserves Romanesque-Mudejar remains and whose bell tower is formed of Bernuy’s old defensive watchtower. Another must-see in this town is the dolmen of the Prado de Las Cruces, the only one existing in the whole province, as well as another thirteen that have yet to be excavated, with which it forms a megalithic cemetery declared a Site of Cultural Interest.

Once you have left Bernuy, the route continues and avoids the AV-500 highway via an overpass for pedestrians and cyclo-tourists from where a four-kilometre descent begins as far as the stream of Prado Casares. From this point onwards, the landscape now changes into a moor strewn with Holm oaks (Quercus ilex), where there are often flocks of sheep of the entrefino breed, and you can enjoy the flight of numerous kites (Milvussp.), common buzzards (Buteo buteo), shrikes (Laniussp.), as well as the presence of crows and other small passerines, such as the black-eared wheatear (Oenanthe hispánica) and the crested lark (Galerida cristata).

When you reach kilometre nine, on the horizon you will see the profiles of the Sierras of La Cuesta and El Malagón, on the left and on the right, respectively, of the trail, on whose crests you can discern rows of modern wind turbines.

Once you have passed the Prado Casares stream, you will come to a Holm oak meadow, where large hundred-year-old specimens stand out and at whose feet there are traditional cattle drinking troughs and several shepherds’ huts.

The trail continues showing travellers unique slate outcrops while they descend towards the River Mediana’s seasonal course, where they can see typical riverside vegetation formed of willows (Salix sp.) and ash trees (Fraxinus sp.).

From this point, you face the final section of the trail which, some 700 m before the end, features its steepest slopes, crowned in the southeast by a rubbish tip, which vultures fly over continuously in their search for food.

The end of the nature trail is located at the north-western access to the town of Urraca-Miguel, where you will find the last of the route’s interpretative panels. In this town, it is worth visiting the church of San Miguel Arcángel, freshening up in the waters of its fountain.

Once you have finished the route, you can continue your trek through the Cañada Real or drovers’ road which, on entering Campo Azálvaro, runs as far as the reservoir of Voltoya or Sorones, some five kilometres from the village. Here, in the winter, you can see countless water birds and, in the summer, steppe species such as stone curlews (Burhinus oedicnemus) and little bustards (Tetrax tetrax).

Another possible alternative is to leave in the direction of the village of Ojos Albos to visit the Second Iron Age cave paintings of Peña Mingubela and the remains of its Romanesque bridge, in a landscape presided by numerous vultures.

Sites of interest

Puntos de interés

Culture

Information

Municipality

Hostel

Passport

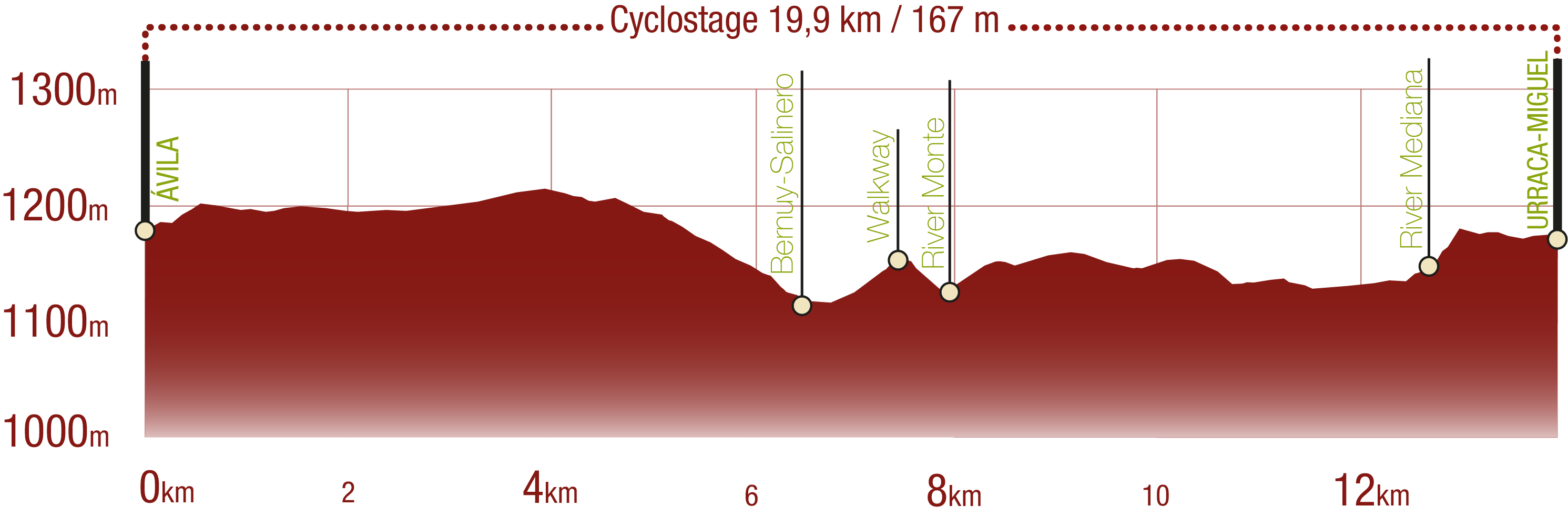

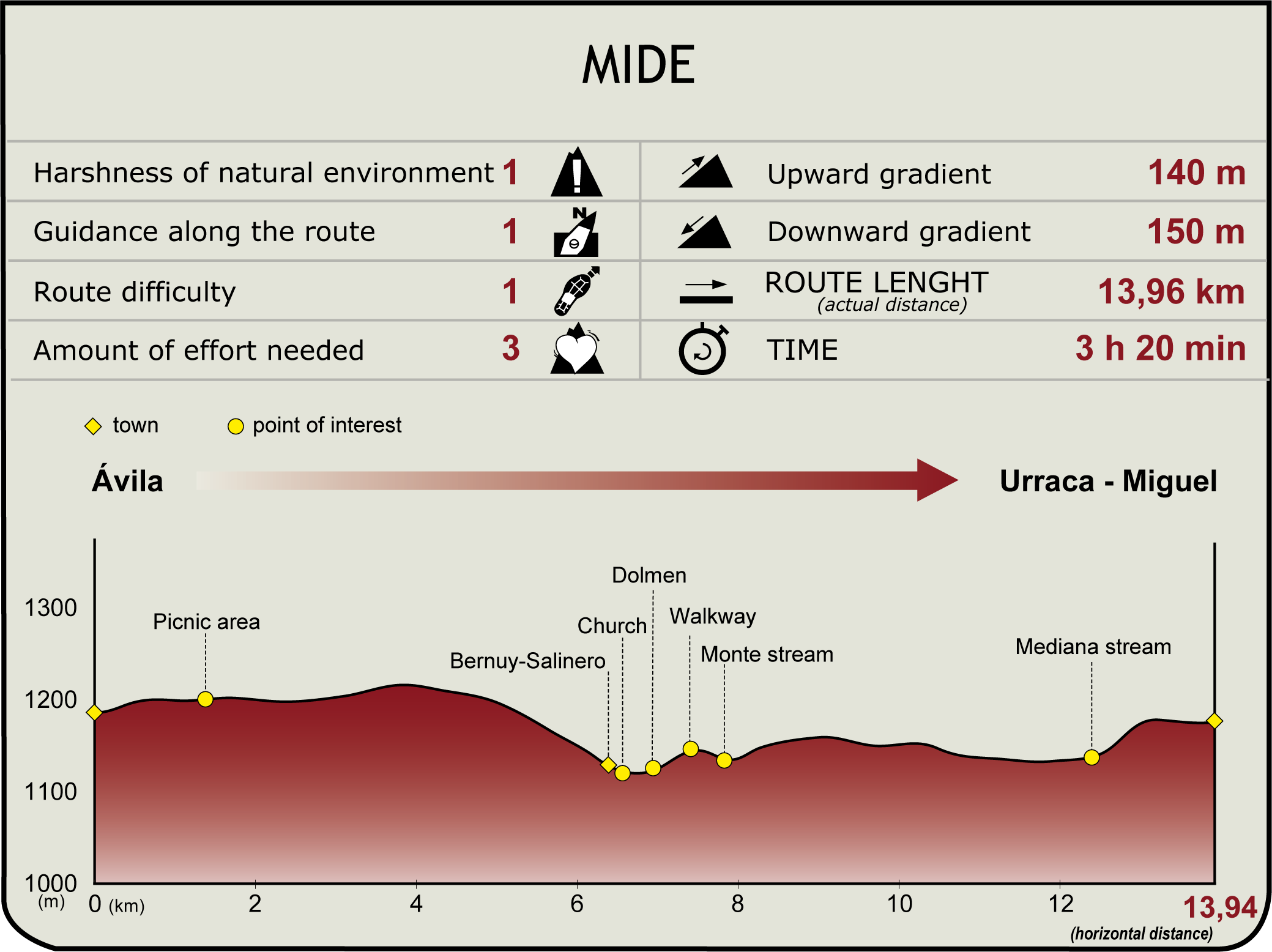

Profile

(Calculated according to the MIDE criteria for an average excursionist with a light load)</

Highlights

Further information

The Prado de las Cruces Dolmen

In Bernuy-Salinero, you can visit the dolmen of the Prado de las Cruces, a megalithic cemetery that was declared a Site of Cultural Interest in 1995. It is a unique example of megalithic architecture in the province of Ávila.

Its typology corresponds to the so-called "corridor tombs", which owe their name to the fact that they are formed of a circular chamber that is entered via a corridor on the southeast, covered by a layer of stones and earth.

This burial place was built between the late Neolithic period and the early Bronze Age, from the last centuries of the 4th millennium to the first third of the 2nd millennium BC.

Drovers’ roads: From transhumance to leisure and preservation

This drovers’ road forms part of a diverse variety of shepherds’ trails, defined according to their widths, such as cañadas, cordeles, veredas and coladas. The largest are the Cañadas Reales, with a width of 90 Castilian yards (some 75 m). In bygone times, thousands of heads of cattle travelled along these “natural highways” in order to take advantage of alternative seasonal pastures and seek protection from inclement weather. The gradual disappearance of the ancient transhumance trade has jeopardized the rich, natural, cultural legacy linked to these trails.

Fortunately, this trend is changing thanks to the new values that are emerging in present-day society, which increasingly demand their use and recovery, not only as open-air recreation areas, but also on account of their importance in the preservation of biodiversity, on acting as biological corridors that link together highly-valued natural spaces and isolated colonies of species that are threatened or endangered.

Multimedia

Downloads

GPS Downloads

Documents

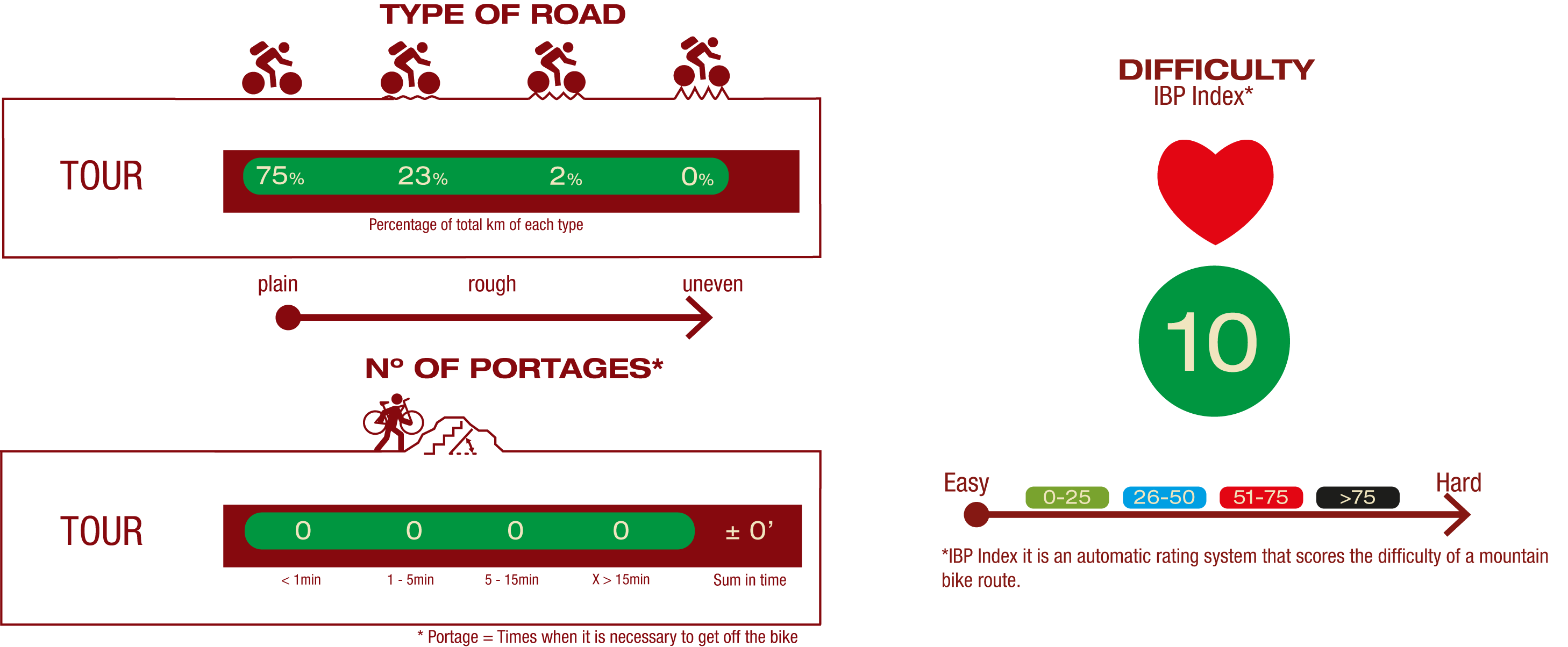

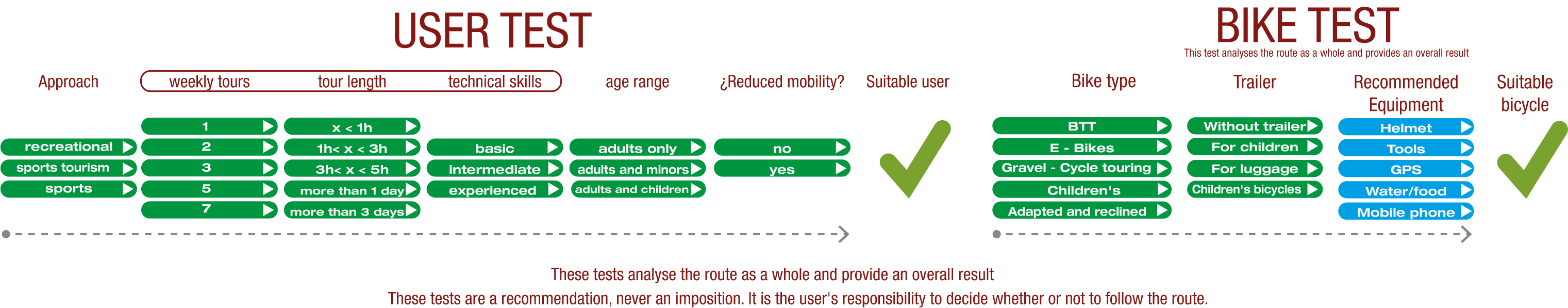

Cyclability

TYPE OF ROAD, PORTAGES & DIFFICULTY

SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS

- The route features eight cattle grids and crosses through the town of Bernuy-Salinero where extra caution is advised.

- It is worth mentioning the elevated walkway that crosses over AV-500 road and several uphill and downhill stretchs of slight slope in the final section of the itinerary.

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

- Find out about the technical aspects of the route and the weather on the day.

- Take care of the environment. Take care not to disturb animals or damage vegetation. Respect private areas.

- You must give priority to pedestrians and comply with general traffic rules.

- The environment in which you will be riding is open, free to move around and an area where many activities are carried out (sporting, forestry, livestock and agricultural activities). Always have an understanding, prudent, responsible and respectful attitude.