Net of Natural

Trails

Stage 23: Villardiegua de la Ribera - Torregamones

Description

Towards Castro de Peña Redonda and San Amede Shrine

This 12-kilometre Stage begins at Villardiegua de la Ribera and ends at Torregamones. The granite cliffs, typical Arribes del Duero, for which this protected area is best known can be seen for the first time on this Stage of the Nature Trail.

The path leaves Villardiegua de la Ribera by a wide, natural gravel track, known as Camino del Picón, and ventures into a place called Escornea, where the landscape is dominated by tall holm oaks (Quercus ilex) and private farmsteads surrounded by stone walls.

The route is escorted throughout by Pontón Creek, whose banks are dotted by former water mills, no longer in use. Although the river runs dry in the summer, in the rainy season the water flows through the bottom of the valley, turning the land along the banks into green pastures.

Small, shallow pools of water along the path are used by livestock as watering holes throughout the year. The nearly permanent supply of water allows bulrushes or cattails (Typha latifolia) to thrive along the banks.

The small ponds are home to tadpoles and marbled newt larvae (Triturus marmoratus), the favourite prey of certain animals, including the great diving beetle (Dytiscus marginalis), a voracious carnivore insect. On the water surface, pond skaters and greater water boatmen eat flies and mosquitoes, whilst dragonflies and damselflies look for a place to lay their eggs.

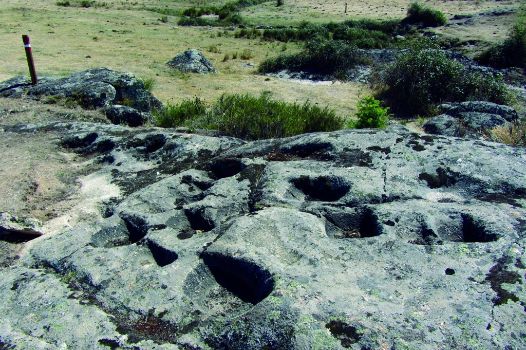

The Trail continues on a small path along the bed of the creek with two traditional stone bridges to cross the river. After passing through a metal gate and past an old mill, the path reaches Valle or Rivera del Pontón mining site, where one can see the hollows in the rock where the Romans washed the rock for gold.

From here, the route drifts away from the creek, and continues along a wider, well-kept track that runs up and down continuously towards the main attraction of this Stage, Castro de Peña Redonda which, according to some sources, was a Vetton village, later Romanised.

The name of this fort, also known as San Amede or San Mamed, derives from a shrine built in the late Middle Ages, which remained standing until the nineteenth century. It was built in honour of San Mamés, saint with widespread devotion among the pilgrims walking the Camino de Santiago. The shrine was built with materials taken from the fort. Some of the elements recovered date back to the Second Iron Age.

From the top of the fort, the Trail begins a fairly steep descent to a valley with a beautiful stone bridge and the remains of a mill. The Trail then begins to climb up the valley towards a metal gate, where the track widens and the last stretch of the Stage to Torregamones begins.

The route continues ahead, ignoring all the offshoot roads that emerge during the climb. It finally reaches a well-marked offshoot road leading to Torregamones’ “chiviteros”, roofed stoned buildings where livestock (nanny goats and kids) were kept.

Before reaching the town of Torregamones, the trail runs along Mimbrero Creek and the old Matarranas Mill, now restored. As with many other local traditional uses, the cultural value of these mills have been prioritised over their economic value, as an important part of the historical, cultural and social past, which is deeply rooted in this corner of the county.

Barely 1 kilometre ahead, after crossing Cualesfondas on the Camino de Azuzeras, the route reaches Torregamones, the endpoint of the Stage.

Enlaces de interés

Profile

Highlights

Further information

Potón Mining Site

Gold was a strategic asset between the first and third centuries. Gold mines of greater importance were state-owned. There are several gold mines in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, including a few in Zamora.

Mining operations in the area of Villardiegua de la Ribera concentrated on a primary deposit, i.e. veins of gold encased in rock, in this case, a quartz dyke.

The rock was crushed and grinded with large stamps (mallets) to release the gold. A row of troughs (buckets) was placed above granite blocks (stampers). The fine sand produced was subsequently rinsed in nearby streams and placed on sloping tables where the gold and quartz would separate.