Net of Nature

Trails

River Ebro Nature Trail

Description

select a stage:

The River Ebro

When looking at a picture of a physical map of the Peninsula, the triangle of the Ebro’s depression – unmistakeable for any schoolchild - stands out from the almost entire north-eastern quadrant. Its influence can even be felt over the entire Levantine coast, as it is the only large river current of the Mediterranean watershed, compared to other causeways on the peninsula of a similar size –Tajo, Duero, Guadiana and Guadalquivir – which flows into the ocean. Its 930 km route makes the River Ebro the second longest river on the Iberian Peninsula, after the Tajo, although its position inside a broad valley and well-defined by mountain chains means it serves as the backbone for 85,000 km², thus forming the most complex, extensive and fast-flowing basin in the territory.

This triangular basin is clearly framed by the Pyrenees to the north and in a westerly-easterly direction; the Sistema Ibérico, on the right side, in a north-westerly / south-easterly direction; the Cordillera Cantábrica, at a north-westerly angle; and the Catalan Coastal chain, to the east and parallel to the coastline. They are mountains with robust reliefs that increase the watershed to an average altitude of 2,000 m.

In Fontibre, where the karst fountains of the River Ebro are located, the montane waters that were previously collected by the River Híjar spring to the surface. A little further on, in Reinosa, the Ebro is joined by the River Izarilla on the orographic right bank. It continues receiving volumes of water from the Rudrón, the Oca and the Oroncillo, on the right, and from the Nela, the Jerea, the Omecillo, the Bayas and the Zadorra, on the left, as far as the Conchas de Haro gorge. Once in the central depression, where it reaches its maturity stage and begins to wander at the foot of mountains and through buttes and other valleys, the main inflows come down from the north: Linares, Ega, Aragón, Arba and Gállego. The Tirón, Najerilla, Daroca, Iregua, Leza, Cidacos, Alhama, Queiles, Huecha, Jalón, Huerva, the modest Ginel and Lopín and the Aguas Vivas tributaries appear on its right bank.

Before the River Ebro settles into the last pre-coastal sierras once again, it collects waters from the Martín, Regallo, Guadalope and Matarraña, on the right, and from the Cinca-Segre mountain range, on the left. These two tributaries, the most fast-flowing in the basin, join together just before reaching the River Ebro, in the well-known Aiguabarreig, a melting-pot of waters, lands and cultures. Close to the sea, the river courses of the tributaries have little volume. The characteristics of the mountain flange also determine the changeable climate in the basin, a varied lithology and a complex water system that feeds the large river, aspects which ultimately determine the biodiversity within it. The climate fluctuates freely between Atlantic and Mediterranean influences, although the mountain belt retains both and boosts continental values. Mild temperatures and abundant rainfall, distributed throughout almost the whole year, come from the oceanic north and extend along the upper course of the River Ebro, reaching the northern part of the Ibérica mountain range and the western half of the Pyrenees. In the latter case, the high summits impose a mountain climate. At the same time, the Catalan Coastal Chain also curbs the merits that come from the Mediterranean, which are only interrupted by cold fronts and summer droughts. Compared to these mild climates, the centre of the basin suffers a drastic drop in rainfall and the harsh contrast between hard winters and midsummer heat. Generally speaking, it is a dry climate, of a Mediterranean type with some continental characteristics, in which heavy evapotranspiration impacts the aridity of the ground, winter fogs reduce the amount of sunshine and increase the sensation of cold and equinoctial instability is characterized by the appearance of a north wind.

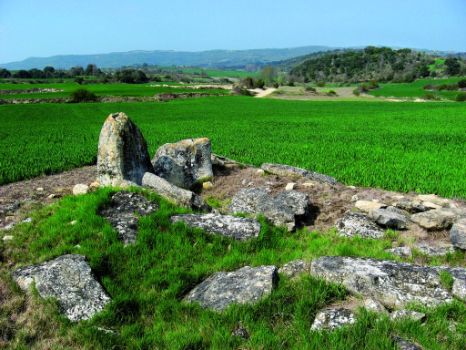

Its lithology is related to the geological history of the basin. Its gestation began some 65 million years ago – in the late Secondary or Mesozoic era and in the early Tertiary era – as a consequence of the orogeny or structural deformation of the Alps. The collision of African and European plates caused significant rock folding and the formation of the mountains that accompany the River Ebro. The River Ebro basin was formed in contrast with the Pyrenees and the Sistema Ibérico, which both stand on marine trenches. This depression was filled with a sea that soon turned into an enormous salt lake. The opening of a corridor in the sierras of the Catalan coast caused it to empty and led to the establishment of the river network that has been operating during the Quaternary era. The role of glaciation was essential in this transformation, which caused intense fluctuations in the sea level and, as a consequence, affected the difference in level between river sources and runoff areas. In this way, the end of the Ice Age caused the formation of the delta.

Because of these tectonics and subsequent erosion processes, several types of rocks have appeared. Sandstones, marls, conglomerates, sands and Mesozoic limestone (basically from the Cretaceous and Jurassic eras) form the basis of the upper stretch of the River Ebro, which is sometimes boxed in in a spectacular manner. In the Tertiary depression, it settled on a bed of clay, sand and evaporate rocks (gypsums, sodium and potassium salts), combined with more resistant layers of limestone, sandstone and conglomerates. Limestone, Mesozoic lands prevail in the Catalan Coastal Chain, after which the detritus materials of the Tertiary and Quaternary eras reappear. The lithology of the rest of the basin also includes metamorphic and eruptive rocks from the Primary or Palaeozoic era in the different mountain ranges.

Such a complex morphostructural arrangement is also the reason why the River Ebro’s water system is also the most complex of all the river causeways on the Peninsula. Its inflows embrace a diverse array of types, ranging from pure snow water to diverse rainfall systems, both Mediterranean and Atlantic, including their possible combinations. In this way, in spite of its status as a Mediterranean river, its behaviour in Tortosa is similar to that of the large rivers in the Pyrenees on the French side.

The magnitude of the basin described above leads to a series of overlapping, countless environments and natural settings (ranging from high mountain to the sea, including the deserts of Bardenas and Monegros). If you only take the River Ebro into consideration, the more than 900 km of its main riverbed embrace a biodiversity that is hard to match, in spite of the significant human intervention that has modified its natural condition and dynamics.

As regards the plant cover that accompanies its course, black and white poplars and willows form the basic triad of the riverside copses and woods. In an outer border, elms, and at the forefront, saltmarsh bulrushes, bulrushes, reeds, rushes and tamarisks populate swamped lands and gravel beaches. Ash trees, creepers, elders, wild rose bushes, blackberry bushes and diverse bushes of theSalix genus end up defining a wilderness of senses. At the present time, these refuges for wild flora and fauna are isolated along the River Ebro, affording shade to deserted banks, islands and river branches, the characteristic galachos or cut-offs of its middle course.

Above and beyond the pipeclay of the river, the valley’s cover diversifies in keeping with changes in the weather and in the land. The Quercus family, formed of holm oaks, gall-oaks and Melojo oaks, is spread across hills and slopes of the upper section, according to the composition of the soil and the levels of sunshine and humidity. Beeches and other mixed forest deciduous trees (hazel-nuts, aspens, maples, sorbs, etc.) are also present. Pine woods accompany the course of the river as far as the Mediterranean. The most common species of pine tree, wild, Aleppo and stone pine, are joined by kermes oaks, mastic trees, buckthorn, rosemary, furze, bearberry, thyme, fescues, etc. even junipers and Savin junipers, plants, bushes and low-size trees that carpet the lower hillside when the forest disappears.

The Ebro Nature Trail

The third largest eco-system is the steppe. Its special features are some of the main attractions and treasures of the Ebro valley. These are gypsiferous and saltpetre lands, barely covered by Russian thistles, white wormwood, broom, esparto grasses, catnip, albaida, ephedra and rockrose, among other species, which are home to rare and endemic plants such as asperillo, creeping thyme, winterfat (Krascheninnikovia ceratoides) and Riella helicophylla, a salad algae. Most of Iberian fauna is represented in this corridor through emblematic species of birds and mammals, both from the interior and from the coast, and via an exceptional chapter of invertebrates, above all from the steppe sphere. The importance of the landscape and the environment of the River Ebro, briefly mentioned in previous pages, can be compared to the anthropological dimension that the river has achieved since ancient times. The Nature Trail weaves both worlds together, the natural and the cultural, the river and its biotopes and the experience, genuinely human, of conceiving and following a route.

Ibero or Hiberus was the river name collected by ancient Greek and Roman reporters, possibly a transcription of the indigenous word “river” which ended up lending its name to the whole of the western European peninsula and, by extension, to its inhabitants. The acculturation processes that resulted from trade colonisation and military conquest evidence an upriver, upstream itinerary. In exchange, this land exploration transported downstream useful knowledge for undertaking new enterprises. Around these dates (7th to 1st centuries BC), the Ebro was already an extremely humanised space. Iberian peoples (Sedetanos, Ilergetes and Ilercavones), Celts (Berones and the Celts themselves from Iberia or Celtiberians) and peoples whose background is difficult to identify, Indo-European or otherwise (Cantabrians, Turmogos, Autrigones and Vascones) could be seen on its banks.

The finding of archaeological pieces that seem to personify a sanctified Flumen Hiberus (a sculptural fragment from the 2nd century; National Archaeological Museum of Tarragona) suggests that the Ebro was regarded as an anthropological place: the river, a dynamic space, converted into a reference for a multitude of peoples, within an extensive portion of land.

People, ideas and objects flowed two ways. In graphic form, the image of this mobility is that of a navigable Ebro, marked out by the ports of Vareia (Logroño), Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza) and Dertosa (Tortosa). The 20th century still bore witness to the hustle and bustle of rafts and other fishing and transportation vessels. The last representatives of this traditional navigation survive on the delta, while canoes and recreational boats are a contemporary replica.

Other divergent paths branch off from these longitudinal ones. The network of Roman roads that entered the valleys and extended across all the corners of Hispania are their oldest reflection. They reused old routes which would serve as the basis for others to come. Bridges evidence that same divergence – there are many of them and from different periods that cross the River – as do others consisting of crossing boats, of which very few survive. But perhaps dykes, weirs, channels and dams are the infrastructures that most influence the idea of separation, on this occasion, between the free behaviour of the river and the human devices that attempt to direct it, to control it. These constructions have contributed to the socio-economic development of the valley, making the Ebro one of the most industrious rivers on the Peninsula. Mills, fulling mills, waterwheels, power plants, factories, waterworks, purification systems, etc. are just some of the handmade industrial facilities forced to establish a permanent dialogue with the river. Finally, the paths are also converging: the tributaries themselves that open up valleys on their descent; the herdsmen that come down from the mountains to the plain; and all the forks on El Camino de Santiago or St. James’ Way that join the Ebro to go upstream and reach Compostela where, in bygone days, the world as it was known ended. This spiritual path has generated exceptional pieces of heritage, such as the Romanesque, which expanded during its mediaeval high point and safeguards one of its founding legends in the Basilica del Pilar in Zaragoza, on the banks of the River Ebro.

These economic, spiritual and archaic nature paths, at any event, are translations of the river current itself. The Nature Trail is the modern-day version of all of them and their successor.

On its route, in addition to the beautiful metaphor on life and regeneration – permanence amid change – evoked by any river, the Nature Trail of the Ebro GR 99 offers you the chance to find a truly powerful creative force, a flow that organizes this entire plural and exciting universe.

Interesting links

- Gobierno Cantabria. Naturaleza y Medio Ambiente

- Fundación Patrimonio Natural de Castilla y León

- Gobierno de La Rioja. Medio Ambiente y Espacios Naturales Protegidos

- Gobierno Vasco. Medio Ambiente

- Gobierno de Navarra. Medio Ambiente

- Gobierno de Aragón. Medio Ambiente

- Generalitat de Catalunya. Medio Ambiente